Return to Today

Margerie Scott

London: Peter Davies, 1961

213 pages

Vanessa Gray and Don Temple met in a streamy wartime canteen. She was an English Rose, working the counter; he was an American serviceman who found her attractive. After Vanessa's exhausting shift, Don hired a cab, whisking them to her Chelsea flat. Once there, Dan warmed a hot-water bottle and tall glass of milk, and Vanessa fell asleep in his comforting arms. The two didn't become lovers that night, but would the next morning. They both knew their's was a was a one-time, two-time, six or seven-time thing.

Don was married to Mary Nell, a "delicate" woman born and raised in his hometown of Kalamazoo, Michigan. I would've used the word "fragile" in place of "delicate." Never in the best of health, Mary Nell was convinced pregnancy would kill her, and so red-blooded American Don had been living a chaste life. Vanessa, single, was struggling with the recent deaths of her mother and RAF pilot brother Brian.

All this is backstory.

The novel's first sentence is far from brilliant, but I like it: "When the letter from Arizona arrived, Vanessa knew it was too late; twelve years too late."

You see, twelve years have passed since the lovers' last tryst, after which Don returned to Kalamazoo. In that time, Vanessa met and married Bill, a cousin of her childhood friend Philip Tennant. Injured in the war, poor Bill expired before their first wedding anniversary... tragically, before he could consummate the marriage. Vanessa now lives in the country, sharing the house in which she's been raised with her father, her elderly nanny, and a housekeeper of sorts named Marie-Teresa.

Don has written to say that he'll be visiting England in September. Because – I'm guessing – he didn't want to splurge on air mail, it is September. Don arrives on the very day his letter is received.

Marie-Teresa, who loves an audience, is positively giddy, whilst nanny refuses to hide her displeasure. The old girl remembers a weekend during the war when this married man dared visit. Vanessa's papa is displeased for much the same reason.

Why is this man visiting now, after all these years?

Don is not so sure himself, though Mary Nell's death must have something to do with it.

The Kalamazooian has never been able to get over his wartime fling. He thinks that seeing her again might exorcise memory and desires. Or maybe, just maybe, he and Vanessa can start from where they left off, Bill be damned!

When Don learns that Bill is dead, he moves quickly in proposing marriage.

Vanessa's acceptance took me aback. Over the previous ninety-one pages, I really thought I'd come to know her.

Return to Today is a novel of disruption – and with disruption comes action. Friend Philip is the first out of the gate. He'd had a wartime tumble with Vanessa himself, after which his own marriage proposal had been rejected. Ever since, sad sod Philip has sat, spending the intervening years thinking that the woman he loves will one day come around. Don's intrusion fires a new campaign to win Vanessa's heart.

Emily, Philip's mother, sees the American's intrusion as a threat to her own plan to wed Vanessa's father.

And then we have Marie-Teresa; what's her reaction? Though a minor character, a refugee of unknown origin, she's is by far the most intriguing. Publisher Peter Davies is spot-on in describing Marie-Teresa as "a loveable dark-haired bundle of complications."

Peter Davies also describes Return to Today as a comedy. I'm not so sure it is, though there was one passage that raised a chuckle. It won't have the same effect out of context, so I won't bother sharing.

Return to Today spans four days, which the author divides into six sections:

- Friday Morning

- Friday Evening

- Saturday

- Sunday

- Monday Morning

- Monday Evening

I recommend reading Friday Morning through Sunday; on Monday Morning the novel begins to fall apart because it's then that Scott really goes for laughs.

This is a shame, because the first four sections had me thinking that Return to Today was certain to make the annual Dusty Bookcase list of books worthy of a return to print.

It won't, which is not to suggest that it isn't worth your time.

A query: On the evening they meet, Venessa tells Dan "some people think my name is odd."

Is it?

Dan thinks so, asking "is it French or something?"

Was Vanessa such an unusual name eighty years ago?

|

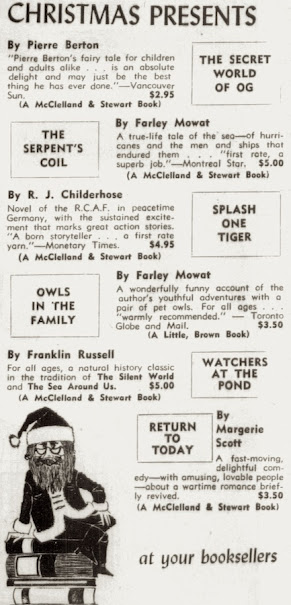

The Windsor Star

2 December 1961 |

Object and Access: An attractive hardcover featuring dark blue boards, the jacket illustration is credited to Val Biro. My copy was purchased earlier this year from the very same UK bookseller who sold me Dove Cottage. Price: £8.00. There's some evidence that McClelland & Stewart published a Canadian edition, but I've never seen it.

As of this writing, two copies are offered for sale online. At £11.75, a jacketless copy of the Peter Davies edition is the cheapest. Ignore that. The copy you want to buy is listed by a bookseller in Ashland, Oregon, who offers the Peter Davies edition and the McClelland & Stewart edition of Scott's second novel The Darling Illusion (1954). Both have jackets. Both are inscribed by the author. The price for this two-book lot is US$44.00.

You know what to do.

Related posts: