The Happy Isles

Basil King

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1923

I nearly let the year pass without reading any Basil King, and started in on this novel only when I remembered that my copy had been given as a present ninety years ago this month.

Not much of a reason, is it.

To be frank, after

The Inner Shrine and

The Contract of the Letter, I'd had enough of Reverend King's gentle preaching on matters of reputation, flirtation, infidelity, separation and divorce. I was wrong to expect more of the same in

The Happy Isles. All figure, of course, but here things edge away from the matrimonial and toward the political.

The novel opens on a splendid spring day spoiled when eight-month-old Henry Elphinstone Whitelaw, of the New York Whitelaws, is stolen from his carriage in Central Park. A tragic event, it calls to mind Isabel Ecclestone Mackay's

The House of Windows (1912), which is built around the abduction of a wealthy Vancouver couple's infant daughter. The balance of this novel, however, owes much more to Charles Dickens than Mrs Mackay.

King's abductor is Lucy Coburn. A young woman "feeble in mind from birth, half-demented by the death first of her husband and then of her child," Lucy took the baby so as to "satisfy her thwarted mother-love."

Love Henry she did, moving about Manhattan, forever fearing that someone might identify him as the missing Whitelaw baby. Good thing, too, because Lucy can't quite keep her story straight; even Henry, whom she calls both Tom and Gracie, is confused:

"I'm a little boy, ain't I?"

"Yes, you're a little boy, but you should have been a little girl. It was a little girl I wanted."

The early years are the easiest, with poor, damaged Lucy living off her husband's life insurance. When the money runs out, she turns to shoplifting. Lucy's luck ends on 24 December 1904, when she is caught lifting a pair of fur-lined mittens that Tom had hoped would be his Christmas gift. The boy spends Christmas Eve in a children's home. The next morning he learns that his "mudda" has suffered a painful death by downing cyanide.

A Merry Christmas to you, Cousin Ida!

Now orphaned – or so the authorities believe – eight-year-old waif Tom is shipped up the Hudson to an unwelcoming foster family in an ugly little town. After a time – an unpleasant time – he is adopted by an unhappy couple who are suffering from a failing farm and failing marriage. King is on familiar territory here. I set aside all earlier complaints in recognizing the chapters that follow as the very finest in the novel.

There be many troubled souls in

The Happy Isles, but not one so well drawn as Quidmore, Tom's adoptive father. An adulterous coward haunted by the road not travelled, he takes inspiration from the story of poor Lucy Coburn in trying to rid himself of a wife, Tom's adoptive mother. Quidmore tries to trick his freshly minted son into administering the fatal dose. When this doesn't happen the farmer breaks down, as much from relief as failure. Quidmore is a man tortured, troubled and torn until wife Anna learns that he's been seeing the local widow. It's only then that he can summon enough courage to do the dastardly deed himself.

Rejected by the widow lady, who is no fool, Quidmore makes himself scarce. He takes Tom to New York, holing himself in the very sort of place Lucy would've considered home.

Remember when I described Quidmore is a troubled soul? Well, he disappears, leaving Tom all his money. I think we can all assume that he took a dive off the Brooklyn Bridge.

Orphaned – kinda – for a second time, the boy is taken under the wing of fellow lodger, one-eyed Liverpudlian Lemuel Honeybun. "A rogue, a burglar, an ex-convict," old Honey Lem gives up his thieving ways and devotes himself to raising young Tom.

It's all downhill from here, I'm afraid. Tom, who has already shown himself to be an A+ student, uses Quidmore's money to pay for Harvard. In his very first class, he's seated next to Tad Whitelaw, the brother her didn't know he had. This is one of the more believable coincidences.

The Happy Isles marks something of a departure for Reverend King in that it ends up as less a comment on marriage than society. In its pages the poor suffer, they work hard and they take risks. Honey Lem dies after being is crushed in a workplace accident.

My apologies for that spoiler.

At Harvard, Tom finds himself surrounded by a privileged, spoiled, ill-behaved lot – and here I include brother Tad. There's more than an insinuation that when inherited, not earned, wealth and position lead to ruin. Socialism is spoken of, but only by goodhearted retired crook Honey Lem. Tom recognizes that it's all so unfair, but can see no solution to what ails the nation.

He's chosen banking as a profession, so one can't expect much.

The Happy Isles was King's penultimate novel. The last published during his lifetime, it first ran from March through October 1923 in

Harper's Magazine. Advertisements for the finished book described the serialization as having "aroused interest almost if not quite equal to the furore which resulted from the anonymous publication of 'The Inner Shrine' by the same author years ago."

Not true.

In 1907,

the furore surrounding The Inner Shrine was front page news in Canada and the United States; discussion of

The Happy Isles was limited to book reviews… of which this is one.

Will there ever be another?

Most interesting passage:

Honey never pawed him, as the masters often pawed the boys, and the boys pawed one another. He never threw an arm across his shoulder, or call him by a more endearing name than Kiddy. Apart from an eagle-eyed solicitude, he never manifested tenderness, nor asked for it.

Object:

Object: A 485-page hardcover bound in green cloth with gilt lettering. I bought my copy – signed, of course – from a New York City bookseller late last year. Price: US$43.86. I'm blaming the missing jacket on Cousin Ida.

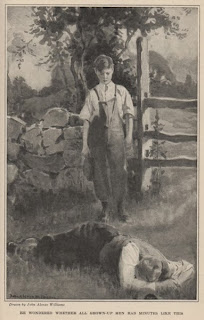

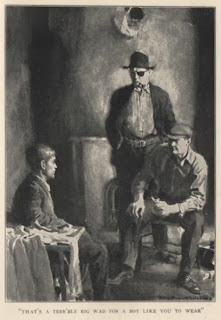

A first edition, it includes four plates by John Alonzo Williams. Knowing there were more, I splurged – ten American dollars! – on the advance copy made up of pages from the

Harper's serialization.

With nine more illustrations, it turned out to be well worth the price. The depiction above of a collapsing Quidmore is one.

Here Tom has a chance encounter with a woman he does not know is his mother:

Access: The Harper first enjoyed no second printing, though a cheap Grosset & Dunlap edition did follow. Hodder & Stoughton released a UK edition in 1924. No reprint there either. The Canadian branch of Hodder & Stoughton appears to have released an edition in 1923 – it was advertised in that November's

Canadian Bookman – but I'll be damned if I can find a trace.

As with nearly all Basil King items, prices are cheap. Very Good first editions,

sans jacket, can be had for US$4.50. Copies of the UK Hodder & Stoughton edition are more scarce, but are only marginally more expensive.

Outside of the Toronto Public Library, we Canadians are served only by our universities.