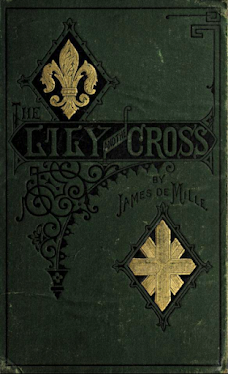

The Lily and the Cross: A Tale of Acadia

Prof. James De Mille

Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1875

264 pages

Like De Mille's A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, reviewed here last January, The Lily and the Cross opens with a vessel adrift on a calm sea. The Rev. Amos Adams (known affectionately as the "Parson") is a New England schooner belonging to Zion Awake Cox (known affectionally as "Zac"). It has been chartered by his friend Claude Motier to voyage from Boston to Louisbourg. Père Michel, a newly-met Catholic priest, is along for the ride. Because the year is 1743, Zac is understandably anxious, considering the French as his natural enemies.

"O, there’s no danger,” said Claude, cheerily. There’s peace now, you know — as yet.”

Zac shook his head.

"No,” said he, “ that ain’t so. There ain’t never

real peace out here. There’s on’y a kin’ o’ partial

peace in the old country. Out here, we fight, an’

we’ve got to go on fightin’, till one or the other goes

down. An’ as to peace, ’tain’t goin’ to last long, even

in the old country, ’cordin’ to all accounts. There’s

fightin’ already off in Germany, or somewhars, they

say.”

The plan had been to make quick, deposit Claude and Père Michel onshore not too far from Louisbourg, then hightail it back to New England. But the wind stopped blowing and a dense fog had moved in, making Zac all the more antsy. Who knows what's out there?

What's out there is a small portion of either a round-house or poop deck – De Mille is only so specific – upon which seven survivors of the shipwrecked French frigate Arathuse stand, sit, and kneel. As three of the seven belong to the French aristocracy, it can't be said that the group is representative of their home country. There's the Comte de Laborde, who isn't much more than a ghost. The sensitive reader will give the author a pass as the character is close to death. Laborde's gorgeous daughter Mimi is far stronger; from the moment of her introduction, we know that she will play a key role in what is to transpire. The other count, the Comte de Cazeneau, just happens to be new governor of Louisbourg. One would think he would be forever in gratitude to his rescuers, but Claude, Zac, and the crew of the "Parson" soon find themselves in imprisoned.

Might the incarcerations have something to do with the comte having eavesdropped on an intimate conversation between Claude and the gorgeous Mimi; the tête-à-tête in which he shared his recent discovery that Jean Motier was not his real father, rather the Comte de Montressor?

Describing The Lily and the Cross in further detail would invite spoilers, but not confusion. The web is tangled, but not so much that the reader cannot foresee the directions and intersections of every thread.

This is not a criticism.

De Mille deserves credit for his ability to keep things straight. The Lily and the Cross is one of those historical novels in which nearly all primary and secondary characters are connected by backstory, spoon-fed over the course of its twenty-six chapters.

The Comte de Laborde and the Comte de Montressor were close friends until they became romantic rivals vying for the hand of the same woman. That woman would become the Comtesse de Montressor, who would in turn give birth to the young man introduced to the reader as Claude Motier. She and her husband fled France for New France, victims of a conspiracy orchestrated by the Comte de Cazeneau, but known to the Comte de Laborde. The latter did nothing to expose the malfeasance, not even after the villain Cazeneau seized Montressor's property for himself. Shortly after the ruined couple's arrival in Quebec, the Comtesse de Montressor died. Her grief-stricken husband wandered off into the wilderness, never to be heard from again. It is presumed he died. The Comte de Laborde's purpose in crossing to the New World had to do with finding the son of the Comte and Comtesse de Montressor so as to make amends. I'll add that the commandant of Louisbourg is an old acquaintance of the Comte de Montressor. As for Père Michel, père is enough to break that code.

C'mon, you knew. You can't say that was a spoiler.

The Lily and the Cross is interesting enough, but nowhere near so much as A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, the novel for which De Mille is best remembered. As a historical romance it is somewhat unusual in that its hero, Claude, is so often reliant on others, namely Zac and Père Michel. At the novel's climax, his execution is thwarted and his freedom gained through the chance arrival of a ship from France.

Okay, that was a spoiler.

At the end of the novel's 246 pages, what strikes most about The Lily and the Cross is De Mille's pandering to the American market. Its subtitle, A Tale of Acadia, echoing Longfellow's Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie (1847), is the least of it. Throughout the novel, France is invariably described as corrupt (which it was), while New England is depicted as pure (which it was not). Old England receives no mention and is therefore spared judgement.

Claude had hired Zac's schooner in an effort reconnect with his French heritage and return to the country of his mother and father, but in the final pages Père Michel, his surviving parent, advises against it (emphasis mine):

"What can France give you

that can be equal to what you have in New England?

She can give you simply honors, but with these the

deadly poison of her own corruption, and a future full

of awful peril. But in New England you have a virgin

country. There all men are free. There you have

no nobility. There are no down-trodden peasants,

but free farmers. Every man has his own rights, and

knows how to maintain them. You have been brought

up to be the free citizen of a free country. Enough.

Why wish to be a noble in a nation of slaves? Take

your name of Montresor, if you wish. It is yours now,

and free from stain. Remember, also, if you wish, the

glory of your ancestors, and let that memory inspire

you to noble actions. But remain in New England,

and cast in your lot with the citizens of your own free,

adopted land.”

Cut to the Rev. Amos Adams – the Parson – on which we find Jericho, very much a minor character:

He was a slave of Zac’s, but,

like many domestic slaves in those days, he seemed to

regard himself as part of his master’s family, — in fact,

a sort of respected relative. He rejoiced in the name

of Jericho, which was often shortened to Jerry, though

the aged African considered the shorter name as a

species of familiarity which was only to be tolerated

on the part of his master.

Would he? Would Jericho have regarded himself as part of the family? His master's family? Zac isn't shown to have a family, and does not treat Jericho as a brother.

I will say this for Zac. He was right about the fighting in Germany.

Object and Access: The novel first appeared in Oliver Optic's Magazine (January-June 1874), a Lee & Shepard publication.

Is my copy a second printing? A third? I ask because I've seen some bound in green boards. Mine features six illustrations credited to John Andrews & Son, a Boston firm that produced work for Lee & Shepard.

As far as I can determine, the novel enjoyed two further editions in the nineteenth century before falling out of print. It was revived in the twenty-first century – 2010 to be precise – as a Formac Fiction Treasures title. It benefits from an introduction by Michael Peterman. Copies can be purchased through this link. At $16.95, they're a steal.

The edition I own can be read online

here courtesy of the Internet Archive. I much prefer the green.

Related posts: