A Terrible Inheritance

Grant Allen

New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, [c. 1890]

A Terrible Inheritance is by far the worst Grant Allen I've read to date. That it's so short made it no easier task; in fact, much of what makes the book so very bad is caused by its brevity. Subplot and character development have no space. The twists and turns found in Allen's best are all but absent – there's precious little room to manoeuvre. Coincidence, ever-present in the man's work, is forced to even more absurd heights. I blame the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, which in 1887 commissioned and published

A Terrible Inheritance as part of its Penny Library of Fiction.

|

from Queer Chums by Charles H. Eden

(London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, n.d.) |

The Society was strict about its Penny Library of Fiction, ensuring that each volume numbered thirty-two double-columned pages. An old pro – he would've been thirty-eight at the time – Allen wrote to measure. Biographer Peter Morton tells us "Allen was able to manufacture featherweight novelettes like these in a few hours, surely without engaging his higher mental processes at all."

A Terrible Inheritance begins with the actions of an idiot, spoiling an otherwise very pleasant garden party at the English country home of Sir Arthur Woolryche. Here are the details: Some upper class twit, a would-be archer seeking to impress, strolls out onto the lawn, draws his bow, and hits the family dog.

The tragedy is made all the worse with the discovery that the arrow, one of Sir Arthur's Guyanese curios, has a poisoned tip.

But wait!

"Mr. Prior's here," somebody answered in haste from the group. "He knows more about poisons and poisoning than almost any other man in all England. He's made a special study of it, as I know. Mr. Prior! Mr. Prior! Come here, you're wanted."

Good luck soon comes to outweigh the bad. Prior is not only an expert in poisons, but is the leading authority on curari, the very one used on the arrow. What's more, just days earlier he had received from South America an elixir that may well prove to be an antidote.

What are the chances!

Prior saves the dog, thus proving the corrective effective. The College of Physicians' awards him its gold medal. Better still, Bertha, Sir Arthur's beautiful daughter, falls for his "manliness and sterling good quality". Father gives his blessing, despite being troubled by the young man's resemblance to… to… Sadly, Sir Arthur can't quite place the face.

Remember, this is the tale of a terrible inheritance, not a happy union. As the wedding day approaches Prior learns that he is the son of a Dr Walter Lichfield, also an expert in curari, who had died in disgrace whilst awaiting trial in the poisoning death of an uncle.

|

The Terrible Inheritance

Grant Allen

London: E. & J.B. Young, n.d. |

Prior releases Bertha from their engagement the next morning. How could he not? By great coincidence, he and Sir Arthur had once speculated as to what had become of Lichfield's infant children. Said Prior:

"I don't know whether my profession makes me think to much of hereditary transmission, and all that sort of thing; but if I were born with a curse like that hanging over me, I'd give up my life entirely to some good for my fellow-men, and expose me least of all to any possible temptation. And I'd never marry."

Prior's only hope is that the man he now knows to have been his father was in fact innocent. Through his investigations, he comes to believe that Arthur Flamstead, Lichfield's close friend, was the actual murderer. Who is Arthur Flamstead? Why none other than Sir Arthur himself. "He assumed the name Woolrych instead, by royal warrant, on the death of a distant cousin on his mother's side, from whom he inherited a certain amount of property," explains Lady Woolrych.

Sir Arthur? A murderer? I didn't believe it for a second, in part because his daughter Bertha is such a sweet girl.

A Terrible Inheritance plays upon Allen's pet theories regarding heredity, something he does to greater effect in

What's Bred in the Bone,

The Devil's Die and

A Splendid Sin. This adds a certain of predictability – a drunkard's offspring will become drunkards, a gambler's offspring will become gamblers, and an expert in curari will spawn experts in curari. Those familiar with Allen will look about the small cast of characters for the true murderer, but find none. Sure enough, the true culprit is introduced in the final chapter.

Do I spoil things more by revealing it all ends with a wedding?

Trivia (for Canadians): Prior doesn't know he is the son of Lichfield because he was an infant at the time of his father's death. His mother soon set sail for Canada, where she and her children lived "under an assumed name in a remote village".

Trivia (for writers): A Terrible Inheritance was the first of three books Allen wrote for the Penny Library of Fiction;

A Living Apparition (1889) and

The Sole Trustee (1890) followed. Writers for the series earned between 30s and £10 per title – roughly £172 and £1150 today. I'm guessing that Allen's pay was at the upper end. Either way, it's not bad for an afternoon's work.

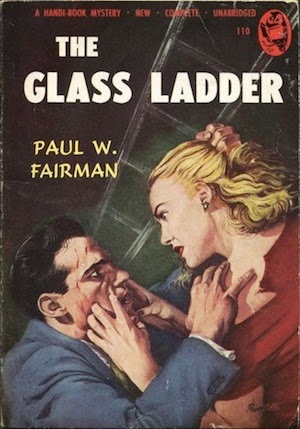

Object: A slim, 57-page hardcover, my copy, the first American edition, was purchased in August from a Yankee bookseller. The frontispiece, by an illustrator named Gallagher, has been simplified somewhat on the cover. Am I wrong in thinking it a novella? Is it a long short story? The word count is 16,226. You decide.

Access: A Terrible Inheritance enjoyed three editions and was later published in Danish (

En underlig arv, 1891), Swedish (

Mordet i Erith, 1917) and German (

Ein schreckliches Erbteil, n.d.). The Kingston-Frontinac and Toronto public libraries have copies, as do the University of New Brunswick, University of Alberta and Simon Fraser University.

Last century, the Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions produced microforms of the Crowell and Young editions.

Both can be read gratis at the Internet Archive. As might be expected, they have attracted a wake of print on demand vultures, who in turn excrete all kinds of mess. Miami's Book on Demand demands US$55.78 for theirs; just under a dollar a page.

|

| Advert for Monkey Brand Soap featured in the E. & J.B. Young edtion |

Related post: